“Speak Truth to Power” – The Story Behind the Burning of the Gaspee, A Film by RIC Alum Andrew Stewart

- News & Events

- News

- “Speak Truth to Power” – The Story Behind the Burning of the Gaspee, A Film by RIC Alum Andrew Stewart

From left, Richard Lobban, RIC professor emeritus of anthropology; Andrew Stewart, Class of 2009; and Carolyn Fluehr-Lobban, RIC professor emerita of anthropology.

When Andrew Stewart decided to make a film about the Gaspee Days Parade to commemorate the burning of a British revenue schooner by colonists, he didn’t know a shadow would be cast on a celebrated event in Rhode Island’s past.

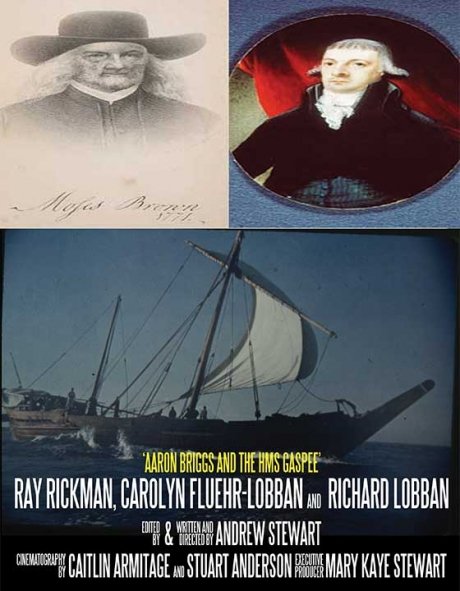

Every June the Gaspee Days Parade is observed in the Gaspee Plateau to celebrate the burning of the British ship HMS Gaspee by revolutionaries led by John Brown. Stewart said that missing from the costumed figures on the floats is African American Aaron Briggs who played a significant role in the 1772 attack. Also lost in the annals of history is the motivation for the attack, Stewart said. “The Gaspee insurrection was not a noble act carried out by brave patriots but by slave traders to protect their interests,” said Stewart. He decided to tell the full story in a documentary called “Aaron Briggs and the HMS Gaspee.”

To make the film, the 2009 graduate who earned a degree in film studies at Rhode Island College, made use of the research done by Richard Lobban and Carolyn Fluehr-Lobban, both professors emeritus of anthropology at Rhode Island College; and Ray Rickman, Providence-based rare book collector.

The film depicts the events that transpired on June 9, 1772. According to accounts, the British captain of the Gaspee attempted to search a ship owned by John Brown – a trader in rum and slaves. Brown’s crew refused to allow the search and took off, purposely veering their boat toward the shallow shores of Narragansett Bay in order to force the British ship to run aground.

Once the Gaspee had grounded, a conspiracy was hatched at Sabin’s Tavern in Providence (which stands today as the Wild Colonial Tavern on Water Street) led by John Brown. The plan was to burn up the Gaspee.

According to Richard Lobban, the motivation behind the rebellion was less then patriotic. “The issue of the day was taxation without representation,” he said, “which meant taxation of the slave trade and rum business. These conspirators, who were also slave owners and slave traders, were fighting for commercial freedom. It was basically a violent representation of their own interests.”

To carry out their plot, Brown pressed Aaron Briggs, a 16-year-old indentured servant of African/Indian descent, into service. Carolyn Fluehr-Lobban said Briggs was probably recruited because he could pass for Indian, and Brown wanted to make the attack appear as if it had been an Indian attack. “The ultimate irony of all of this is that a slave was forced to fight for a slave trader,” she said.

Briggs was told to row Brown out to the Gaspee, accompanied by the co-conspirators in seven other longboats. In the ensuing encounter, the captain of the Gaspee was shot and wounded and his ship set on fire, after which the conspirators returned to Providence. However, Briggs rowed back to the Gaspee to throw his lot in with the British in the hope of being emancipated. After assessing the situation, however, he decided to return to his master’s house.

Considered an act of treason, the incident was investigated by the British Royal Commission. When questioned, Briggs turned state’s evidence against the conspirators.

Stewart explained why. “If you’re in Briggs’ position, you’re thinking, okay, if John Brown and the others are convicted of treason, their slave trading will come to an end, and I’ll gain manumission.” But historical records show that Briggs was returned to his master and Brown returned to his lucrative business of trading rum for slaves.

Stewart said that his goal for the film was that the truth be told. “The Browns basically turned a little village that was Providence into a city built by revenue from the slave trade,” he said. “They built Providence Bank, which became Fleet Boston and is now Bank of America. They built the College at Rhode Island, which became Brown University. They established the infrastructure of the government, because they were also involved in political machinations. People say that Roger Williams founded Rhode Island, but if anyone built it, it was the Brown family. The goal of this documentary is, as the Quakers say, to ‘speak truth to power.’”

For the Lobbans, the project is a life’s dedication to uncovering the complexities of race, class and gender in American history. “As recently as a few decades ago, Aaron Briggs was not on the radar screen,” said Fluehr-Lobban. “Putting his story back into American history – the real complex and contradictory story of the American experience – is so important.”

See film at http://tinyurl.com/HASCBriggs.