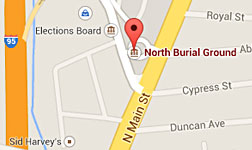

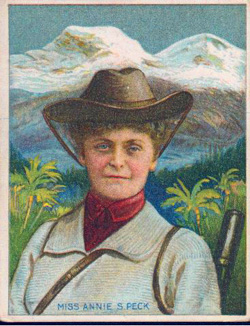

Annie Smith Peck was born in Providence, RI on Oct. 19, 1850, and grew up in the family home at 865 North Main St. She attended local schools and graduated from Rhode Island Normal School (now Rhode Island College) in 1872. She taught high school briefly in Providence and elsewhere, including Saginaw, Michigan, then enrolled in the University of Michigan in 1875. She graduated first in her class three years later, with a degree in Greek and Classical Languages, and earned an M.A. in Greek in 1881. From 1881-1883 she taught archeology and Latin at Purdue University, then studied German and music in Europe for two years, and in 1885 became the first woman to study at the American School of Classical Studies in Athens. Afterward she was appointed professor of Latin at Smith College. She resigned her position at Smith in 1892 to become a full-time lecturer, first in Greek archeology and then on the subject which had become her hobby: mountaineering.

Though her family had vacationed often in the White Mountains and the Adirondacks, Peck only took up serious mountain climbing after a visit to Switzerland in 1885. In 1888, she ascended Cloud’s Rest (10,000 ft.) in the future Yosemite National Park, and Mount Shasta (14,162 ft.) in California. Between 1890 and 1894 she also scaled various peaks in New Hampshire’s Presidential Range. In 1895 she became only the third woman to climb the Matterhorn, and conquered several other Alpine peaks as well. In 1897 she climbed Mexico’s Popocatepetl, and then turned to the country’s highest peak, Mount Orizaba (18, 700 feet). But Orizaba disappointed her. Though she set a woman’s altitude record, she did not feel it was a particularly difficult climb; indeed, the editors of the New York Sunday World, who commissioned her account, were equally disappointed in the lack of excitement in the story. She then became determined to a summit higher than anyone had ever climbed before—in particular, higher than any man.

After several frustrating years of fundraising (she raised only about $1200 of the $5000 she felt necessary, through donations from friends in Providence and also earned by taking on assignments from the New York Times and the Boston Herald, and accepting sponsors like “Peter’s Chocolate”), she sailed south in July 1903 to make an attempt on Mt. Sorata (21,276 ft., also known as Illampu) in Bolivia. Her goals were to verify the mountain’s height and to make various other meteorological and geological observations; thus she equipped the expedition with the latest scientific and mountaineering equipment. Though she reached 15,350 feet, the expedition failed to summit—due in part to unreliable guides, and to the substantial failings of a male scientist she had hired to accompany her. It would not be the last time her male companions failed to measure up. One could attribute this in part to her own lack of leadership, but as she herself later noted, “One of the chief difficulties in a woman’s undertaking an expedition of this nature, is that every man believe he knows better what should be done than she.” On her return to La Paz, she did successfully climb El Misti, an active volcano in Peru (19,199 ft.), but this peak presented no particular challenge. A second attempt on Sorata in 1904 was no more successful but more dangerous; at one point she found herself precariously and unexpectedly balanced on the edge of a deep crevasse, and turned to find that her two guides had untied her connecting rope—exposing her to certain death with one wrong step.

Peck next set her sights next on Mount Huascaran in the Peruvian Andes, South America’s second highest peak at 22,205 feet and one many believed to be unclimbable. She hired another in a long string in incompetent male companions (she referred to him only as Peter), and reached 19,000 feet, only to be forced back by the threat of avalanches. A second attempt by a different route (without the intractable Peter) was no more successful, while a third effort in 1906 also failed, again plagued by her inability to raise adequate funds (she accumulated only $700 of a desired $3000). After this effort she began a somewhat serendipitous search for the origins of the Amazon River and in the process succeeded in reaching her first peak in South America, a mere foothill of 16,000 feet.

It took Peck three more attempts, but she finally reached what she believed to be the summit of Huascaran in 1908. Even then things did not go smoothly. She had finally succeeded in hiring two more competent, conscientious male comrades, but one of them (Rudolph) broke climber’s etiquette by racing ahead of Peck to be the first to reach the summit! The descent was a more horrific experience than the climb itself, and Rudolph lost most of one hand and half a foot to frostbite. And severe winds caused Peck to miscalculate Huascaran’s height--and in fact she had only reached the shorter north peak of the mountain at 21,812. Her great mountaineering rival, Fanny Bullock Workman, determined to preserve her own reputation (she had reached 23,300 in the Himalayas), hired engineers who established Peck’s correct altitude. Still, this was at the time the highest climb in the western hemisphere, and the Peruvian government renamed the peak Cumbre Ana Peck. Peck continued her conquest of the Andes by climbing Mt. Coropuna in Peru (21,079) where she planted a banner trumpeting a cause she had long championed: “Votes for Women.”

Annie Peck continued to climb for almost the rest of her adult life; her last successful attempt was on Mt. Madison, in New Hampshire, a mere 5,636 feet. She also steered her energies in new directions. In 1929-30, at a time when airlines had just begun passenger flights, she embarked on a seven-month air tour of the South American continent. In 1934 she enjoyed cruises to the West Indies and to Newfoundland. And in 1935, at the age of 84, she set on a world tour. She became fatigued while climbing the Acropolis in Greece, returned home, and died on July 18, 1935.

While Annie Peck may be remembered most commonly for her landmark achievements in mountaineering, she was also a woman of no small intellect, a prolific author and a tireless advocate for causes close to her heart. In addition to her expertise in classical languages, she was fluent in Spanish, Portuguese, and French; she gave several addresses in Spanish to South American geographic organizations and professional women’s groups. She was a prolific author. Harper’s Magazine commissioned several articles on her climbs from her between 1906 and 1909, and she wrote similar accounts for several other magazines and newspapers; her dispute with Workman was openly pursued in various issues of Scientific American in 1910. Peck published a lengthy account of her Andean exploits in The Search for the Apex of America: High Mountain Climbing in Peru and Bolivia, including the Conquest of Huascaran, with Some Observations on the Country and People Below (1911). She wrote a statistical handbook on the continent, Industrial and Commercial South America (1922), and a traveler’s guidebook, The South American Tour: A Descriptive Guide (1913). Her climbing accounts provide much detail on her meticulous preparation for expeditions, on the often frustrating search for funding, and on the frequently punishing conditions she experienced during her climbs. Finally, she published a journal of her aerial tour of the continent, Flying Over South America: Twenty Thousand Miles by Air (NY, 1932). She helped found the American Alpine Club, and was a member of the Royal Geographic Society and the Society of Women Geographers.

Peck demonstrated her quirky individuality and pioneering feminism in other, smaller ways as well. She climbed in trousers and other clothing suitable for the outdoor adventurer, rather than in the more restrictive, gender-defined clothing she was expected to wear. She designed her own climbing boots. And the American Museum of Natural History loaned her Robert Edwin Peary’s suit of animal furs, which she lost in her aborted 1904 climb of Mt. Illampu. A champion of women’s rights throughout her life, Peck pioneered a highly successful, publicly celebrated career previously reserved for men—and many of the men who did accompany her, as guide and companions on her various climbs, proved unable to match her mettle. She was the subject of articles and reviews in The New York Times, and the state of Rhode Island finally, belatedly, gave her the recognition she was long due when in 2009 she was inducted into the Rhode Island Heritage Hall of Fame. Her death was noted by obituaries in several publications, but the Times gave her perhaps the highest praise, quoting from an earlier article in the magazine Athenaeum: “She has done all that a man could, if not more. She had sagacity, and with it ‘nerve’ and ‘grit’.”

Bibliography and Further Reading:

Rebecca A. Brown, Women on High: Pioneers of Mountaineering (Guilford, Ct., 2002).

Elizabeth Flagg Olds, Women of the Four Winds: A Celebration of Four of American’s First Women Explorers (Boston, 1985).

Milbry Polk and Mary Tiegreen, Women of Discovery: A Celebration of Intrepid Women Who Explored the World (NY, 2001).

Russell Potter, “Annie Smith Peck,” http://www.ric.edu/faculty/rpotter/smithpeck.html

Marion Tinling, Women Into the Unknown: A Sourcebook on Women Explorers and Travelers (Westport, Ct., 1989).

The largest collection of Peck’s papers is The Annie Smith Peck Collection, at the Brooklyn College Library.

Rebecca A. Brown, Women on High: Pioneers of Mountaineering (Guilford, Ct., 2002), 176.

Annie Smith Peck was a pioneering scholar, mountain climber, writer and women’s rights advocate who broke numerous barriers to women’s equality. Born in Providence on Oct. 19, 1850, Peck grew up across the street from the NBG in the family home at 865 N. Main Street. A graduate of Rhode Island Normal School (now Rhode Island College), she later attended and graduated first in her class from the University of Michigan. Peck taught archeology and Latin at Purdue University and, after two years of study in Europe, became professor of Latin at Smith College. She conquered several of Latin America’s most dangerous peaks, including Mexico’s highest peak, Mount Orizaba; Mount Huascaran in the Peruvian Andes (South America’s second highest peak at 22,205 feet); and Mt. Coropuna in Peru (21,079 feet), where she planted a banner: “Votes for Women.” She organized and financed her own expeditions, a task made difficult by prevailing sexism. Male expedition members frequently failed her, often causing her to turn back before summiting. “One of the chief difficulties in a woman’s undertaking an expedition of this nature,” she wrote, “is that every man believes he knows better what should be done than she.” Peck wrote extensively about her accomplishments and also authored books on South America. Inducted into the Rhode Island Heritage Hall of Fame in 2009, upon her death in 1935 the New York Times noted: “She has done all that a man could, if not more. She had sagacity, and with it ‘nerve’ and ‘grit’.” Read More...

Annie Smith Peck was a pioneering scholar, mountain climber, writer and women’s rights advocate who broke numerous barriers to women’s equality. Born in Providence on Oct. 19, 1850, Peck grew up across the street from the NBG in the family home at 865 N. Main Street. A graduate of Rhode Island Normal School (now Rhode Island College), she later attended and graduated first in her class from the University of Michigan. Peck taught archeology and Latin at Purdue University and, after two years of study in Europe, became professor of Latin at Smith College. She conquered several of Latin America’s most dangerous peaks, including Mexico’s highest peak, Mount Orizaba; Mount Huascaran in the Peruvian Andes (South America’s second highest peak at 22,205 feet); and Mt. Coropuna in Peru (21,079 feet), where she planted a banner: “Votes for Women.” She organized and financed her own expeditions, a task made difficult by prevailing sexism. Male expedition members frequently failed her, often causing her to turn back before summiting. “One of the chief difficulties in a woman’s undertaking an expedition of this nature,” she wrote, “is that every man believes he knows better what should be done than she.” Peck wrote extensively about her accomplishments and also authored books on South America. Inducted into the Rhode Island Heritage Hall of Fame in 2009, upon her death in 1935 the New York Times noted: “She has done all that a man could, if not more. She had sagacity, and with it ‘nerve’ and ‘grit’.” Read More...